These Two Leading Ladies Have Left Broadway Behind, But Not Their Love of the Theater

The two women couldn’t know it back then, as they sang and danced eight shows a week, but they would spend the majority of their lives achieving even more significant personal and professional success, all in the Nutmeg State.

Fast-forwarding from those Great White Way glories to 2018 finds Schweid leading Play With Your Food, a Westport-based theatrical company she co-founded 14 years ago, while Libonati does likewise with Summer Theatre of New Canaan, which she started just about the same time.

Both raised families in Connecticut, where they’ve lived for 30-plus years, with each of their two adult children immersed full time in the arts [see “Following Mom” sidebar]. Schweid recently had a book published on creating staged readings, with Libonati founding and continuing to run her Performing Arts Conservatory of New Canaan, teaching young people how to sing, dance, act and believe in themselves.

Leading ladies, indeed…

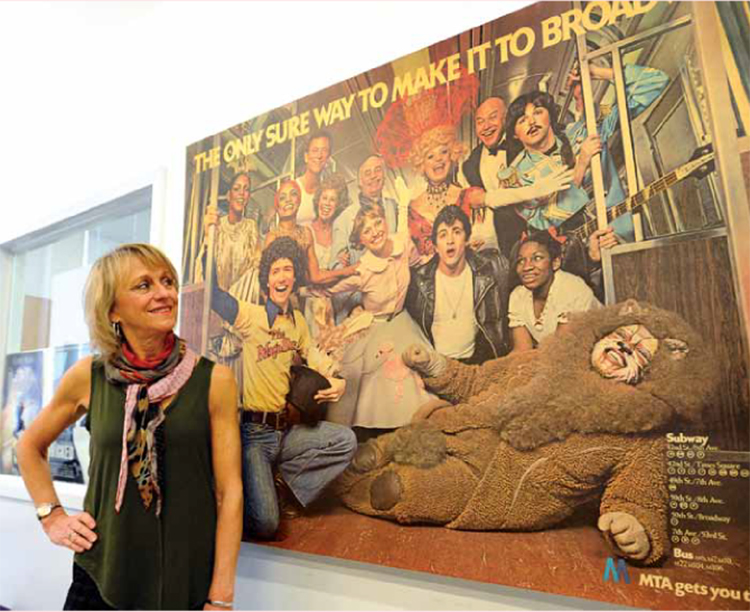

Carole Schweid and Melody Libonati

Beginnings

Growing up in Maplewood, New Jersey (Schweid), and Corning, New York (Libonati), singing and dancing were regular aspects of family life.

“My mother was a singer who performed at hotels and special events, and sang a lot at home,” says Libonati, 65. “She loved musical theater, so all the records in the house were of those. I started singing when I was 4, and sang Sunday school songs on the radio by myself at that age. In fourth grade I was in a play, had the lead and decided that’s what I wanted to do forever.”

She would follow her brother Gary to nearby Ithaca College and its acting program. She met Ed Libonati there; they would eventually marry. Gary and Melody went to New York to act around 1976, and would play Jack and Jill on Broadway in Babes in Toyland. Not long after, Libonati landed Grease.

Schweid, 71, had a more meandering journey. Her life from early on was always about dance.

“I can’t remember ever not dancing,” she says. “I was born to it. I have a theory that if you’re in the arts you get one thing that’s a gift, and dancing was mine. My mom liked to dance, and we would dance in the kitchen.”

Schweid attended Boston University for two years, then transferred to the Juilliard School’s dance department.

“I studied modern dance and ballet there,” she recalls. “You learn technique or you die; how to get out of your feet, how to lift.”

Singing lessons, acting lessons, summer stock shows and other plays followed, as Schweid began her professional career.

Melody and Carole’s Children are Following in Their Moms’ Footsteps

“I was doing off-Broadway shows, one after another. I was a gypsy,” she says. “I went to an audition for Minnie’s Boys, a 1970 Broadway musical about the Marx brothers, at the Imperial Theatre, and won a job in the chorus. At the end of the show we would all walk toward the audience. The Imperial was where I had seen my first Broadway show, and was on its stage the first time I auditioned for a summer stock play. On opening night all of a sudden it hit me that I’m on that same stage, for real. I started to cry, and cried through the finale, the curtain call and the next 20 minutes in the dressing room. That was my first professional Broadway experience.”

Minnie’s Boys was not a hit, and Schweid spent the next few years perfecting her craft, performing in shows all over before her big break would come. She was doing Fiddler on the Roof at a dinner theater in New Jersey. In the chorus was a friend, Nick Dante, who was working after-hours with Michael Bennett on a musical idea about dancers.

Right place, right time

Schweid treasures her past and accepts her present good naturedly, meaning she has ceased protesting consistently being introduced thusly: “This is Carole Schweid. She was in the original A Chorus Line.”

“It’s history, it’s theater lore, and I was there,” she says. “I was in the room where it happened, to quote Hamilton. Sometimes strangers hug me when they find out. I’m not kidding. Because it affected a lot of people’s lives.”

It affected Schweid’s life too, in every way. Before ascending to the plum role of Morales, who sings What I Did for Love, the play’s emotional climax, Schweid personified what the story was about — dancers scrambling to land jobs in a play’s chorus.

She’d been recommended by Dante to Bennett, A Chorus Line’s director and co-choreographer, who in 1974 was workshopping the production.

“Two performers had left, and I’d auditioned for Michael for another show about a year before,” she says. “I went in and danced for him for like 40 seconds and got the job.”

The job was being in the chorus of A Chorus Line, and understudying several roles.

“There were nine of us who covered all the parts, who got cut [in the opening number],” she says. “We had a little booth and would sing in the wings. They always need more voices [for group songs]. And I went on for people sometimes.”

There was no question A Chorus Line would be a hit, because its pre-Broadway run downtown sold out and word spread. Opening night at Broadway’s Shubert Theatre, July 25, 1975, was a frenzy of excitement for Schweid and her friend, Marvin Hamlisch, who composed the music and would become a giant in the industry.

“He had been the rehearsal pianist for Minnie’s Boys,” she says. “He was so great. Opening night he calmed us all down before the show by playing the Chorus Linesongs as if they were written by different composers. Years later at his funeral in New York, Bill Clinton was the first speaker, and he said that Marvin used to do that for visiting dignitaries at the White House. He was such an ambassador for bringing people together. Brilliant, and funny.”

After a solid but unspectacular start to her career, Schweid suddenly was an original cast member of one of the biggest hits in Broadway history. It was both exhilarating and pressurized. After a year or so there would be a second production in Los Angeles. Many of the Broadway cast originals, including Priscilla Lopez, who played Morales, left for the West Coast. Replacements were needed.

“I didn’t want to go to L.A. and sit in the booth there because I was already sitting in the booth in New York,” Schweid says. “Michael had hired someone else to replace Lopez. I was in his office and he said, ‘I’m not letting you play Morales because you’re not Puerto Rican, yada yada.’ ”

Another actress took over the part, but started missing shows and was fired. Schweid was tapped, suddenly front and center for every performance.

“Looking back, it was wonderful and it was horrible, but I wouldn’t have missed it, of course,” she says. “When you take over a part, you have to do it like the person you replaced. They want you to be that person. So I became the Jewish Puerto Rican.

“I was under a lot of stress. I didn’t talk on the phone because I was afraid of losing my voice. The songs I sang were out of my range and I was shouting. I needed them lowered half a tone, but didn’t have the confidence to ask.

“It was great to sing What I Did for Love, but four hours later I would wake up in the middle of the night going ‘ahh-AHH’ to see if I could hit the note. Then not talking all day because I was afraid of not hitting the note.”

Schweid performed Morales for close to a year, validating the toughness and resolve she’d developed early on. Ironically, her steely determination to make every curtain cost her a role in the film Annie Hall, which would win the Oscar for best picture in 1978.

“I was cast for a scene that was going to shoot in Brighton Beach, but they could not guarantee I’d get to the Shubert by 7:30, so I passed,” she says. “I didn’t realize that a movie was forever. It was a real missed opportunity.”

Bennett eventually decided to return the role of Morales to a Hispanic actress. “They said I could go back and cover all the parts, but I declined,” Schweid says.

She did manage one everlasting achievement — singing on the original A Chorus Line cast recording. “On some songs everybody is singing, and I’m one of the everybodies,” she says. “The royalties are not nearly enough, but I’m in one of the pictures in the CD, so that’s pretty nice.”

Grease was the word

Libonati’s memories of being a “Greaser,” as cast members called themselves, are purely joyful. There was no make-or-break pressure because the show had been running for several years before she joined the cast. Like Schweid, she would start as an extra and earn her way to front and center stage.

“I went to an open [casting] call with hundreds of people,” she remembers, as new performers were needed to replace ones who left. “I was hired and went on the road first, on the national tour, understudying for everybody.”

Having to learn all the songs, dance moves and dialogue for multiple roles proved pivotal decades later when Libonati founded Summer Theatre of New Canaan.

“It started me on a more long-term, overall understanding of how things worked,” she says. “For directing, when you have to know everything; it got me interested in not just myself and what I’m doing on stage but what others are doing.”

Libonati’s Broadway Grease run almost ended before it began.

“We did the whole East Coast on the national tour, and then it was going out west,” she says. “I didn’t want to go, so I told them I was leaving. They said if I quit I’d never work the show again. But instead they brought me back to New York to the Broadway show, where I filled in again for a while, and then played [the lead role of] Sandy.

“It was so fun, so fun. We were all kids the same age, everybody having the times of their lives. I played opposite Patrick Swayze, then Adrian Zmed and then [Rowayton native] Treat Williams. We’d all go out to Studio 54 after the shows. It was the start of the whole club thing.”

Libonati would play Sandy for more than two years, nailing it show after show.

“One of the best compliments I ever got from a director was that I was consistent,” she says. “They want things to be the same, which is hard in an acting situation because you have to be in the moment, where it’s really happening for the first time.

“There’s magic in a live performance. That’s why people do it. It’s a sense of something happening right now, that you’re involving the audience, and there’s this great communication working.”

During her Sandy years, Melody and Ed married. One night she arrived at the theater feeling ill.

“The stage manager had had a baby not long before,” she says. “I went up to her and said I felt really bad. She asked me if it made me nauseous to brush my teeth. I said, ‘Don’t even talk about that.’ She said, ‘You’re pregnant.’ And I was. That’s how I found out. I still went on that night.”

Connecticut beckons

With Schweid and Libonati having experienced the bright lights, it was nearing time for something new in their lives, but each would land one more big role first.

For Libonati, it was a recurring part playing a teenager on the soap opera One Life to Live in 1978. Soaps ruled daytime television in those days. For most of the year she doubled up.

“I would go to the studio in the morning, the taping was over by late afternoon and I’d do Grease at night,” she says. “I always had a lot of energy. I was a runner back then. I used to take the script with me and learn my lines while jogging around Central Park.”

Schweid stayed on stage for her final triumph.

“The year after A Chorus Line I did four off-Broadway shows for ego-mending,” she says. “Then I auditioned for the national tour of Pippin, which had just ended on Broadway after a five-year run.”

Schweid went from working with one legendary director/choreographer, Bennett, to another, Bob Fosse, who would direct the musical Chicago, as well as the films Cabaret and All That Jazz, among others. Fosse was casting the Pippin tour.

“He didn’t know me; I walked in and auditioned for the part of Fastrada, a leading role, and got it,” she says. “I remember him asking me about my family background. They want to get to know you because they’re going to spend a lot of time with you and want to make sure you’re not crazy. I was a real dancer and very confident. So it was thrilling to get feedback from him. He went back to the original choreography for me because I could do it.”

Once the tour ended Schweid returned to New York, renewed a romantic relationship she’d begun before she left and married six months later. Sons Max and Dan arrived in 1984 and 1986. When they were still young the family moved to Westport.

“I liked that the town had a history of supporting theater and writers,” she says. “I also liked that Paul Newman lived there! I had no idea how gorgeous Connecticut was. Such open spaces. I love to go to the small art museums all over the state. Plus the food is good, and that always counts.”

The Libonatis had a daughter, Allegra, and a son, Christian, in Manhattan, also in the 1980s, and likewise decided Connecticut was the right place to raise them.

“We researched a 50-mile radius around New York City because Ed still worked there,” Libonati says. “Neither of us had ever been to Connecticut. We didn’t even know where it was. We wanted a sense of community, a place we could be a part of. I wanted my children to be my primary goal and focus. When we found New Canaan the search was over. We wanted a healthy, natural lifestyle, with clean air, trees, grass and a backyard. We’ve been here 33 years so I guess we love it.”

Back to work

As their children grew, Schweid and Libonati yearned to perform again, but not full time. So both wrote one-woman shows.

“I had my own nightclub act, Unchained Melody, with a nine-piece band and two back-up singers, that I performed at clubs in New York,” Libonati says. “But I also did it for the New Canaan Nature Center, our church and at local schools for their benefits. It was all about my life.”

Schweid’s show took a different approach, focusing on renowned choreographer and author Agnes de Mille.

“She’d choreographed Oklahoma! and wrote these great books,” Schweid says. “I adapted stories from them and got her son’s permission to perform them on stage. I created this piece, Agnes, and did it for six years, at every women’s club, every library. I did it at the Smithsonian, and on the Quick Center stage at Fairfield University. It was one of the ways I kept myself sane, by writing and creating something.”

Once Schweid and Libonati’s children left for college in 2003-04, both were ready for something new. Their histories proved they did not think small, and what followed backed it up.

Libonati started the Performing Arts Conservatory of New Canaan.

“I’d earned a teaching degree in college, strictly as a back-up plan,” she says. When the Libonatis first moved to New Canaan she developed the performing arts program at a private high school in nearby Stamford, where from 1991-2004 she directed plays and musicals, and taught musical theater, acting, dance, speech, and singing to hundreds of high school and middle school students.

The Conservatory was immediately successful from its 2004 beginning. Libonati says its goal is to awaken, nurture and grow each student’s creative abilities in the performing arts by offering professional training, workshops and performance opportunities.

“Our slogan is ‘Performance skills for life,’ ” she says.

The same year she started the Conservatory she also founded Summer Theatre of New Canaan.

“There had been a summer theater in town but it was gone,” she recalls. “I brought together community leaders and asked if the town needed a new one. They said yes. It’s a nonprofit so I had to familiarize myself with fundraising, and establish a board of directors.”

Each season it presents one Broadway-caliber musical, with professional performers, along with other plays, mostly for children. The shows, actors and creative teams have continually been nominated for and won Connecticut Critics Circle honors.

“We also have an educational program with Summer Theatre,” Libonati says, “a junior company, high school training and intern program, and our special needs DramaRamas. That’s what I’m really proud of, not just that we’ve won awards.”

Schweid’s 2003 launching of Play With Your Food, with co-founder Nancy Diamond, was a bit more happenstance. The clever title refers to watching staged one-act readings with professional actors following an upscale, restaurant-sourced buffet lunch. It’s the mid-day version of dinner theater.

“I was in a Westport arts committee meeting with Nancy and we started talking,” Schweid says. “We said let’s try something with one-act plays, staged readings [holding scripts], and food, put them together and see what happens.”

Schweid had always enjoyed reading short plays, so she chose the ones to produce as artistic director. Three one-acts of 10 to 20 minutes each comprise a show. Diamond handled working with eateries, the public relations and ticket sales.

What started as a few dates in Westport has grown to include Fairfield, Greenwich and other towns, from January through April.

“We keep it short, from noon to 1:30,” Schweid says. “Then people go back to their day, having had a fulfilling experience.”

As an expert in producing one-acts, Schweid wrote a book about it, and last year Staged Reading Magic was published. It draws upon her experience and expertise to provide an instructional guide. It explains how to transform simple script readings into theatrical showcases, for little cost.

“Staged readings are like opening nights with a script in your hand,” she says. “They should have all the excitement and vitality of a full performance, but with the spontaneity of a good rehearsal. There is a sense of uncertainty in the air because no one knows what’s going to happen.”

Together … finally

The first meeting of Schweid and Libonati, two people expert at figuring things out quickly in auditions, couldn’t have been scripted better. The ladies were aware they would co-star in this story, but the photo shoot one Sunday morning at the Performing Arts Conservatory in New Canaan was their first face-to-face meeting.

Even with people listening in and their being photographed, the women clicked from hello, totally at ease while trading career stories and sharing details of their lives with each other.

Schweid: “Did you ever work with [choreographer] Pat Birch?”

Libonati: “Of course! She was amazing. She did Grease, and is still around.”

Schweid: “She played Anybodys in West Side Story. Not the original role. That was whatsername … Lee Theodore! She used to come to ballet class, put a cup of coffee next to the bar, a cigarette in the ashtray and plié.”

Libonati: “And all the piano players had their ashtrays next to the pianos. They would play hanging over toward them.”

Schweid: “I can’t believe I never met and talked to you.”

Libonati: “I know! I heard about your theater group but have never been. I will come now.”

On it went. Libonati then summed up their lives.

“Carole and I never thought we would be running theater companies,” she says. “And the fact that we are female never hindered or stopped our thoughts and plans. It is wonderful to see that we have become leaders in the arts. And I find it very special that we are able to lead communities in a cultural experience.”

Life really does sometimes imitate art. For these two women, reflecting on all their singing and dancing, the kids raised, the teaching, the plays directed, the businesses run, the book written, the auditioning highs and lows and so much more … to slightly tweak A Chorus Line’s most compelling song lyric, they won’t forget, can’t regret what they did for love.

This article appeared in the July 2018 issue of Connecticut Magazine. Did you like what you read?